Plant ecophysiologists study how plants sense and respond to environmental cues, such as light, temperature, and water availability. Our group investigates these processes in natural and controlled terrestrial ecosystems, evaluating their resilience and ability to acclimate to environmental changes.

Why study plant cold hardiness in a warming world? One of the most pressing concerns in biology is how plants in cool climates will respond to rising seasonal temperatures. Complex feedbacks mean that crop responses to warmer conditions could either hinder or enhance production. Our lab tackles this uncertainty by examining the physiological responses of crops and related species to changing temperatures and water stress.

Major research questions

Can we manipulate ice nucleation in plants to mitigate frost injury?

Frost-sensitive species have a limited ability to tolerate ice formation in their tissues. These species avoid ice formation by supercooling below 0°C to avoid ice formation. Conversely, frost-tolerant species have adapted to cope with prolonged ice formation in their tissues and use this mechanism to survive frost events. Injury in these tolerant species arises from the degree of freeze-dehydration of cells and subsequent rehydration during a thaw. The presence of ice nucleation active bacteria can prove beneficial for the establishment of ice formation in freezing tolerant plants and devastating to the survival of frost-sensitive species. In the past we explored how winter cereal crowns have developed a tissue-level ice formation strategy to protect critical meristem tissues and survive exposure to sub-zero temperatures.

Our current research in grapes (Vitis spp.) characterizes how different under-vine soil amendments aimed at improving plant nutrition could influence spring canopy temperatures. Bare soil under vines promotes the capture of thermal heat during the day and its release overnight. The use of dense undervine cover crops and mulches could result in cooler canopies that are more susceptible to frost injury. Our research will monitor vine temperatures, characterize organ-specific differences in microbiomes, and employ infrared thermography to better characterize how ice nucleation persists through freezing avoidant floral buds.

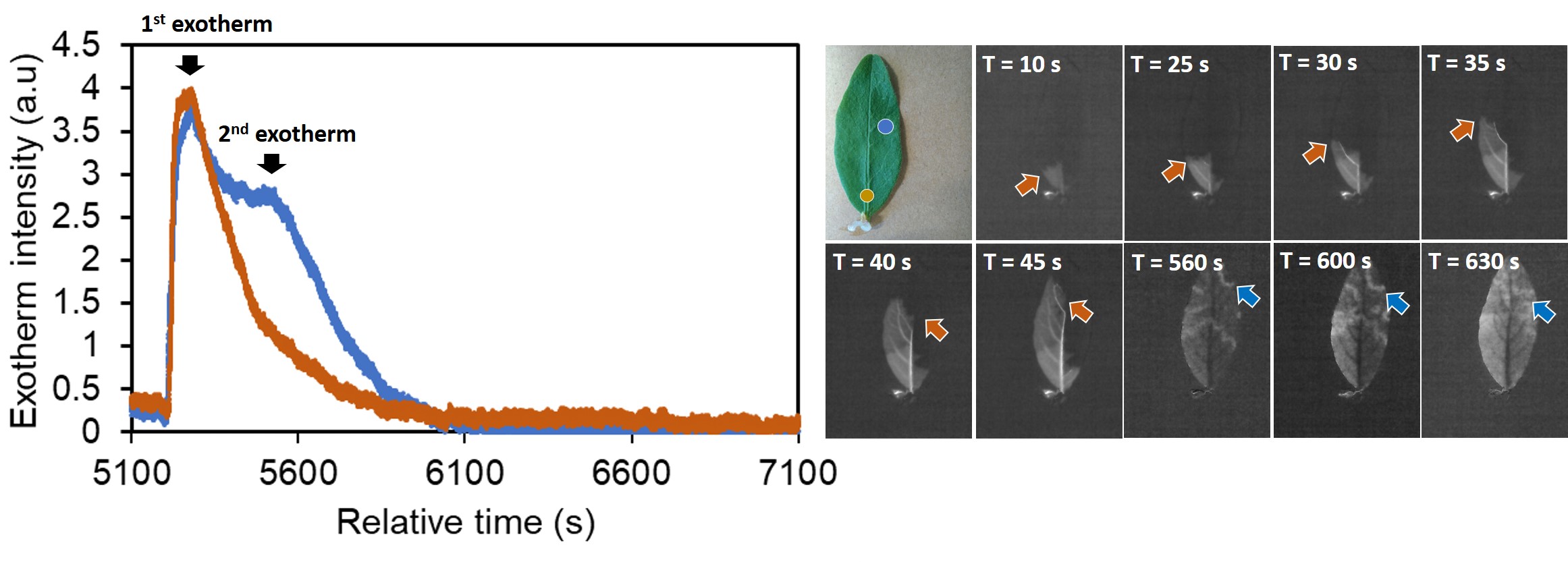

Two exothermic peaks were observed using infrared video thermography in haskap leaves cooled to -4°C. The first exotherm (orange) propagates through bulk water in the xylem over a period of seconds. A second freezing event (blue) occurs over a period of minutes and propagates through the lamina in a wave like pattern.

Can we optimize management strategies to mitigate the loss of cold hardiness?

Our program is investigating the effects of fall pneumatic defoliation in apple orchards. Defoliating apple trees two weeks before harvest can enhance red blush by increasing fruit exposure to light and cooler night temperatures. However, leaves serve as both carbohydrate-producing organs and receptors for photoperiodic and temperature cues that trigger cold acclimation. Excessive leaf removal may reduce the tree’s overall cold hardiness.

We are also examining the impacts of fall tillage in vineyards. Compared to spring tillage, fall tillage occurs when soil moisture is typically below field capacity, reducing the risk of compaction, and soil temperatures are more favorable. However, fall tillage can disrupt surface roots, potentially injuring vines as they acclimate to cold and enter dormancy.

Funding is generously provided through the Agricultural Climate Solutions – Living Labs Project, Grape Growers Association of Nova Scotia, and the Nova Scotia Fruit Growers Association. Projects are conducted in collaboration at the vineyards and orchards of producers in the Annapolis Valley, NS.

In-row alternative tillage (left) and non-tillage control (right) treatments applied to a test vineyard in the Annapolis Valley (Nova Scotia, Canada).

Will silicon fortification enhance the tolerance of grapevines and strawberry to biotic and abiotic stress?

Grape growers in Nova Scotia recognize the need for an effective nutrient management program but have typically minimized inputs due to excessive vigor in hybrid varieties. Developing sustainable practices for Eastern Canada must account for cool soils in early spring that limit nutrient uptake. Additionally, synthetic fertilizers are not permitted in organic farming systems.

Our research assesses whether foliar silicon (Si) amendments reduce injury from abiotic stress and insect herbivory. The application of Si-based amendments is a common agricultural practice to increase bioavailable Si (monosilicic acid, H₄SiO₄). This primes plants and enhances resilience to insect herbivory, pathogens, high/low temperature, humidity fluctuations, or salinity stress. Bioavailable H₄SiO₄ is absorbed from the soil by root cells or from foliar applications by stomata, hydrathodes, or cracks on the leaf surface. Upon uptake, H₄SiO₄ polymerizes into an immobile silica gel (SiO₂·nH₂O). We are interested in evaluating whether the development of a Si-cuticle double-layer within the leaf tissue provides an enhanced physical barrier to environmental stressors. Our research incorporates techniques such as scanning electron microscopy and attenuated total reflectance (ATR) Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy to evaluate how cuticular modifications enhance plant tolerance to high/low temperature, dehydration, or salinity stress.

Our research has expanded to assess how Si-based foliar and soil amendments influence strawberry yield, fruit quality, and strawberry plant tolerance to water deficit stress and insect herbivory.

Funding is generously provided by the Government of Canada.

What are the molecular mechanisms that induce cold acclimation?

Cool season plants cold acclimate when pre-exposed to fall environmental cues, undergoing a series of physiological and molecular modifications. Higher fall and winter temperatures will extend the growing season and delay fall senescence. This uncoupling of short-day length from cooler nighttime temperatures can disrupt the senescence of aboveground foliage and the induction of cold acclimation.

We aim to understand in switchgrass (Panicum virgatum) the molecular basis for the local adaptation of cold acclimation. Switchgrass is a perennial biofuel crop that has undergone limited breeding in the past. In particular, we are focused on the divergence between the northern upland and southern lowland ecotypes. Northern upland switchgrass is more cold hardy but produces less aboveground biomass as compared with the more southern lowland ecotypes. We will use RNA sequencing and physiological profiling to develop a more mechanistic understanding of how cool-season plants respond to rising temperatures. This work will identify novel traits of interest that can be used to identify populations with optimal biomass and cold hardiness traits

Current research in switchgrass is moving forward in collaboration with Dr David Lowry’s research group (Michigan State University). This research is supported by the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center and the US Department of Energy.

Drone image of switchgrass populations at Kellogg Biological Research Station (Hickory Corners, MI). Photo credit: Robert Goodwin.